“The whole future of farming depends on a sustainable system.”

William Pitts

Farmer

Combating Climate Change

Helping farmers do the

Agriculture

Meet William Pitts, a British farmer leading the way in restoring soil health and soil carbon sequestration and storage while tackling yield plateaus and weed pressure. Discover the inspiring story of how sustainable farming methods and collaboration can help making agriculture more resilient to climate change.

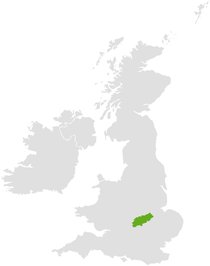

In the heart of Northamptonshire, England, lies a landscape so picturesque that it could easily be mistaken for a scene from a fairytale. If it were a storybook, the main character would be William Pitts, a farmer whose feet have worn the paths traced into these rolling hills and vibrant green fields. However, this idyllic scenery does not reveal the ever-present challenges farmers like William face today that make the biggest job on Earth even more challenging.

Northamptonshire is a county in the East Midlands of England. Agriculture is the principal land user with over 75% of Northamptonshire’s land area in farming.

“I have been farming in Northamptonshire for most of my life,” says William Pitts. “When we started, everything was less complicated. Today, there are so many challenges – climate, soil health, profitability, a growing population – that we cannot continue to farm like we did for the last decades.” That’s why William and his brother Andrew became early adopters of technology to their 2,000-acre farming business, trying to bring high yields and productivity in balance with biodiversity and soil health. “My brother and I took over from my father, who started farming in the late 1950s. He was a fairly forward-thinking man, and I guess we’ve inherited a little bit of that,” the farmer explains.

When the idea of “Project Fortress” emerged, discussing the challenges of yield plateaus and weed pressure with BASF, the Pitts brothers did not need much convincing to participate. “We’ve been working with BASF for 15 years and during this time, the importance of sustainability has increased immensely,” William Pitts highlights.

“The whole future of farming depends on a sustainable system.”

William Pitts

Farmer

The project derived its name from the field where it was being implemented, which had an interesting backstory. In 1943, during a practice flight, two B-17 Flying Fortress planes collided, and parts of the wreckage landed in the field. Consequently, the field came to be known as Fortress.

“Project Fortress is a project at The Grange Farm in Northamptonshire. Since 2021, we investigate there how we can improve the soil by increasing soil carbon sequestration and storage in Fortress Field. Our methods include assessing different rotations, cultivations, and inputs over five years,” explains Alice Johnston, Sustainability Manager for BASF Agricultural Solutions in the UK. “We are happy to have William and Andrew as our host farmers who help us carry out our interventions that also include biodiversity measures such as creating pollinator habitats.” Ultimately, soil carbon sequestration is a way to mitigate climate change through agriculture. “We aim to help farmers achieve higher yields alongside protecting biodiversity and soil health and, through innovative and sustainable farming practices,” says Alice Johnston.

After decades of intense agriculture with short rotations, Fortress Field was in a poor condition: “Farmers are increasingly facing yield plateaus, which they can’t seem to overcome. For decades, agriculture has exploited the land and we’re faced with soil degradation. We have to do something about it and cannot move on like before,” explains Alice Johnston. For about four years now, different types of cover cropping have been tested on the field. “We compare cover crops in different rotation timings. Together with our experts, we then analyze which measures have had the most positive effect,” Alice Johnston adds.

One of these experts is Jenni Dungait, Soil Health Consultant and Honorary Professor at the University of Exeter, UK. “Every year I come to Fortress Field and take soil samples. I measure carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, micronutrients etc. And so far, all cover crops have had positive effects,” she points out. “And building carbon through planting different crops and using herbal leys has led to additional benefits, such as improved water management.”

“The soils now absorb more water when it rains, reducing flooding and retaining water when it gets dry.”

Jenni Dungait

Soil Health Consultant and Honorary Professor at the University of Exeter, UK.

William Pitts adds that all cover crop scenarios tested have suppressed weed species and fostered biodiversity: “Most striking for me was when we discovered that growing a medium-term, multiple-species grassland has sequestered more carbon than any other system we’ve tried. So, if you want to put carbon back into your soil, for the most degraded areas you would need to invest in longer term interventions, before bringing back into cropping. The soil has started to repair very quickly, and the weed burden looks to have virtually fell away.” Project Fortress was able to show that what’s good for the environment also helps farmers tackle their challenges in doing the biggest job on Earth.

As the sun dips below the horizon of the thriving fields of the Grange Farm, it might seem like the end of the story. But William Pitt’s farm is just one chapter in the transformation of agriculture, and the stories of other farms adopting new ways of farming will complete the book.

Published September 23, 2024 by Tanja Rolletter (BASF Agricultural Solutions)

For media inquiries or to repurpose the story, please contact julian.prade@basf.com